Using data to guide refactoring efforts

“This code base is a mess, we need to spend more time on refactoring”. Chances are, you’ve heard this complaint from developers in your team on more than one occasion. Probably even said it yourself a few times. And while most of us can sympathize with a statement like this, the analysis usually doesn’t go much deeper than that. Way too often, the next step is simply to put your noise cancelling headphones on, roll up your sleeves and dig into it, randomly refactoring pieces of code that happen to cross your path. I think we can do better than that.

Across our industry, there seems to be a fairly wide consensus that refactoring efforts should be integrated with regular development activities as opposed to being handled as separate stories on the backlog. Martin Fowler calls this opportunistic refactoring and Uncle Bob refers to it as following the boy-scout rule, but in essence this approach means that you let product priorities drive what parts of the code base you refactor. The payoff for a refactoring effort strongly depends on how often you will make a change in that area in the future and, in absence of a crystal ball, product priorities are a decent indicator of that.

This makes a lot of sense, but what it fails to tell you is how much time you should spend on refactoring as part of a single product feature. Gut feeling seems to be the most common approach. A slightly more structured tactic could be to agree on a fixed percentage as part of the total story estimate. However, both of these strategies can lead to refactoring efforts in places where it does not make the biggest impact. Which highlights the main challenge with refactoring: It’s really hard to know when to stop.

Refactoring is commonly an unbounded task with no clear acceptance criteria making it very easy to go down a rabbit hole where the refactoring effort takes a ridiculously long time compared to the actual feature that started it all. Adding to this, refactoring suffers from diminishing returns where the first 20% is likely way more valuable than the last 80%. The challenge, of course, is to know what constitutes those 20%.

Luckily, there are a few simple steps you can take to make this decision more data-driven.

Start by calculating how often the source files you want to refactor are modified. This can easily be done using your git log in combination with some command line wizardry:

git log --pretty=format: --name-only | sort | uniq -c | sort -rg

Next, grade the code quality of the files, either using a metric such as cyclomatic complexity or by assigning it a subjective score according to some scale (e.g. 1-5, good/average/awful, WTFs per minute, etc.).

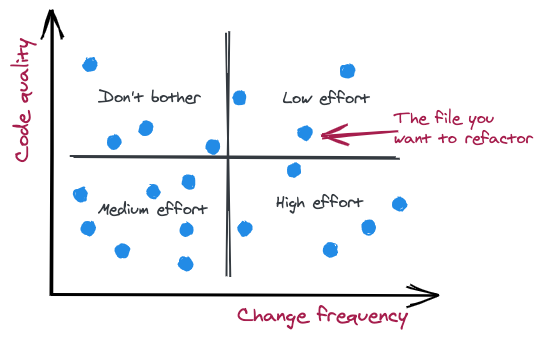

Based on the code quality and change frequency, you can now plot this in a graph as illustrated below.

Divide the graph into four quadrants and let this guide how much time you spend on refactoring.

- Bottom-right. This is where you want to spend most of your total refactoring effort as these are files that are changed a lot and have bad code quality, giving your investment in code quality a higher likelihood of paying off.

- Bottom-left. Bad code quality, but not very frequently changing files justifies a medium refactoring effort. Why not low, you might ask? After all, these files are not touched very often. Well, this can of course be argued, but in my experience this category adds to the team’s overall cognitive load and reduces their ability to understand and reason about the system as a whole, even though the actual change frequency is low.

- Top-right. Good code quality and high change frequency justifies some refactoring, but not that much compared to the previous two quadrants. Due to the diminishing returns of refactoring, the high-value 20% are probably already addressed making further efforts less valuable.

- Top-left. Good code quality and low change frequency. These are the ones you can safely ignore from a refactoring point of view. By all means adhere to the boy-scout rule and make small adjustments, but don’t place your high stake refactoring bets in the area.

By using these simple heuristics, you can make your refactoring efforts more data driven and greatly increase the probability of spending your time where it has the most impact.